From shopping at the colonial goods merchant? How can it happen that the global capitalism dominated by the West is still largely based on structures established in colonial times is symbolized today by the cheaply imported avocados, mangos or passion fruit that pile up in the displays of the shopping center of the colonial goods trader - Edeka for short. In addition to the seemingly banal persistence of such brands, which are interwoven with European colonialism, relations between the global North and countries of the global South are still characterized by unequal power relations at all levels.

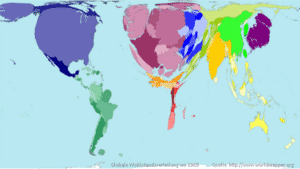

Western societies and the ruling global class possess economic, political and scientific power. They also dominate media coverage and benefit in many ways from postcolonial structures and relations of dependency. These appear particularly drastic with regard to the global distribution of wealth. While countries of the global South are increasingly being bled dry, the money store of the so-called West is literally inflating, so that today 0.9 percent of the world's population owns 43.9 percent of global wealth. The poorer 56.6 percent, on the other hand, own only 1.8 percent of this wealth.

Such glaring social inequalities result from a tightly woven web of Western dominance of international capital and product markets. Citizens of the Global North not only represent the world's most important customers and thus significantly influence supply; through unfair trade agreements and double standards in doing business, the West contributes to further entrenching structures of disadvantage.

While Lindt in Switzerland produces fine chocolates with cocoa beans from West Africa and Cameroon's and Ghana's markets are literally flooded with subsidized wheat, milk powder and the cheapest chicken drumsticks, countries of the Global South miss the chance to establish independent markets and to produce complex products from their raw materials.

This multi-layered system of protectionist practices and subsidization of one's own products by Western markets, while at the same time opening up and developing the global South as sales markets, means that the small farmer in Zimbabwe or the coffee producer in Colombia always remain dependent on the Western-dominated world market. In addition, the self-image of the West as the savior of the world or trustee of peace is maintained by around one hundred and fifty billion dollars of development aid money mobilized annually by the OECD, while old images of dependency remain.

How can you imagine this structure?

You may think of the relationship between the global North and South as a seesaw or a paternoster, where more of one always leads to less of the other. And who would deny that he or she does not benefit in many ways from such an imbalance of power? The freshly brewed coffee in the morning, the bargain offer at large fashion chains like H&M or the advantageous exchange rate in other European countries are so commonplace for most of us that they are no longer perceived as privileges. Privileges that at the same time always go hand in hand with structures of injustice and precarious realities of life.

In a world as complex as ours, it seems a logical conclusion to retreat into a shell of nationalism and detachment from reality, given our co-responsibility as citizens of the West in the daily world events of slash-and-burn agriculture for more cattle grazing, famine in the Middle East due to geopolitically motivated wars, and mountains of garbage in Indonesia. But given the multi-layered pervasiveness of each individual's life and the multiple crises of the globalized world resulting from our lifestyles, it is increasingly difficult to put on blinders and simply carry on as is …weiter lesen

Author: Leah Priesenger